Angry mobs, cheering and jeering. Passionate pleas for change. Tears.

No, it’s not college football. It’s Dr. Allison Shutt’s HIST201: Doing History course, where students learn as they play Reacting to the Past (RTTP) role-playing games — including Rousseau, Burke, and Revolution in France 1791 about the French Revolution and The Threshold of Democracy: Athens in 403 BCE about the origins of Western democracy.

Though the contexts are different, the big questions are similar.

“Students learn about politics in crisis as they face fundamental issues about government and society,” said Shutt, who began incorporating RTTP into her teaching about four years ago.

The games include all the elements of a rigorous Hendrix class — challenging texts, big ideas, and ethical complexity — and also immerse students in novel situations that compel them to test the ideas they’ve read about and discussed and apply them to changing (and often unpredictable) events.

Role-playing is a useful way for people to learn other historical mentalities than their own, according to Connor Johnson, a junior history major and religious studies minor from Detroit, Michigan.

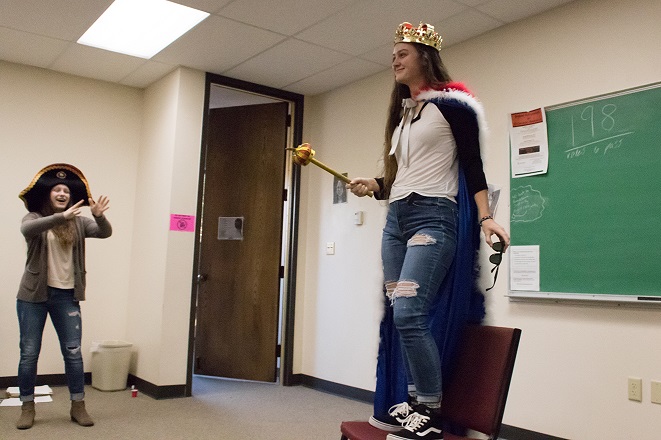

In the games, students are assigned character roles with specific goals and must communicate, collaborate, and compete effectively to advance their objectives. In the process, students become intellectually and emotionally animated. They debate, they compromise, and they scheme. They think on their feet. They pull out their texts and read relevant passages to their colleagues to explain their actions and bolster their legitimacy. They get loud. They learn.

For senior Mary Nail, a history major with a lifelong passion for theatre, a role-playing history course was a natural fit.

“It’s just such a different approach to learning history,” said Nail, who also took the class last year and is a student mentor this fall. “Almost all other history courses at Hendrix (and most other institutions) take form in either a discussion- or lecture-based class structure, so learning history through such a hands-on way that students really get to take ownership of is so unique.

“I chose to be a mentor because I enjoyed the course so much as a student,” Nail said. “Now I’m able to help guide students and give strategy advice, [but] it can sometimes be difficult to hold my tongue when there are parts of the game that they need to figure out for themselves.”

“I want them to develop their own problem-solving skills, but I also want to warn them of potential consequences,” she said. “I enjoy encouraging them because I do not think they realize their strengths and I want to bring that out of them.”

For the most part, beyond a little advice and encouragement from mentors and the professor, students are on their own.

“What is so magical is that the students are in control of the class once the game begins,” Shutt said. “From my point of view as an instructor, I am there to watch students work things out. The best thing I can do is stay out of their way and let them figure it out … and they do! It’s a very different learning experience for them, and it’s a very different teaching experience for me.”

“It’s definitely something I’ve never really experienced in other courses, but it happens so naturally in Doing History,” Nail said. “Most often, students tend to forget that Dr. Shutt is even in the room. Students really like to take ownership of the class.”

“It felt weird at first,” said Rader Francis, another of the student mentors. “But after the first game session we didn’t hesitate on what to do to start the class each day, or on where to take it.”

The course draws a different kind of student — from quiet and thoughtful to more outgoing students, from history majors to non-majors, from gamers to non-gamers. There is no pre-requisite, so first-year students can take the course too.

One obvious difference from more lecture-intensive courses is the amount one is expected to talk with other students.

“The whole experience is a lot more participatory than the typical reading- or lecture-style course,” said Johnson.

Some students take the class to improve their public speaking skills.

“It has been rewarding to see people develop into more confident students,” she said. “I enjoy encouraging them because I do not think they realize their strengths and I want to bring that out of them.”

There is a high level of student engagement, emotionally and intellectually, said Shutt, adding that she especially enjoys seeing shy students come to life when they are put into a role.

Nail agreed.

“I wasn’t expecting to be so invested in my character and the game, especially because the first character I played was a Royalist in the French Revolution,” Nail said. “Students definitely become very connected to their characters.”

“The students were way more engaged with the material,” Francis said. “Everybody wanted to be knowledgeable so they wouldn’t lose the game.”

Though fun, the games are embedded in rigorous scholarship. Solid preparation is the key to winning the game.

“If students are playing well, they’re reading outside of class,” Shutt said.

“Though there is a large amount of work outside of class and core-text reading — Rousseau and Plato are some dense dudes — what I love about Doing History is that the homework never feels like work,” Nail said. “Students spend multiple hours every week outside of class meeting with their groups, but they are having so much fun scheming and strategizing to get ahead in the game that they never really complain about the work.”

Role-playing games can require a greater investment in understanding the historical content and a competitive nature, said student mentor Megan Bellfield.

“In order to do well in each session, you must know the values of each faction and how that affects the government,” she said. “I enjoy a little competition, and I think that helped drive me to be more engaged.”

Role-playing also allows students to stumble and struggle in order to have a deeper understanding of historical context, said Bellfield.

Hendrix alumnus Dr. Nick Proctor ’90, a history professor at Simpson College, a liberal arts institution in Iowa, is also a proponent of using games in teaching.

Proctor will return to his alma mater in March 2020 to work with Shutt and her students, running a simulation another history game-in-development for a course Shutt is developing on game design.

The course is part of Shutt’s work under the College’s James and Emily Bost Odyssey Professorship, a three-year award she received last year.